With community support, the last skipjacks have the wind at their backs

From left, Bob Shores, Stoney Whitelock and Newt (Photo By: Jim Robertson)

JULY 2022

by Steven Johnson, Staff Writer

If a wave could talk, it would sound like Stoney Whitelock, a low, lilting rumble giving voice to the treasures and flotsam it collected on its inbound journey, cresting with power and force, and hoping to catch the listener in its undertow for another compelling performance.

It’s hardly surprising that a wave should sound like Whitelock, a grizzled waterman of the Chesapeake Bay, given all the time they’ve spent together — the better part of seven decades at this point — oystering, crabbing and sailing in tidal waters aboard low, flat, wind-powered skipjacks.

“It started at Momma’s Sunday dinner table,” he says. “That’s all the men talked about, was these boats. That’s all they did. That was their life, five or six generations back. Some of it stuck in there with me and I couldn’t wait to get on one of the old boats and start oystering.”

“It started at Momma’s Sunday dinner table,” he says. “That’s all the men talked about, was these boats. That’s all they did. That was their life, five or six generations back. Some of it stuck in there with me and I couldn’t wait to get on one of the old boats and start oystering.”

Now, the task for the last of the skipjack captains is to prevent those waves from receding so they resound with future generations and preserve the 140-year legacy of the lone commercial sailing fleet remaining in North America.

The center of those efforts is Chance, Md., on the marshy spit of Deal Island, just 3 feet above sea level. It is home to the Skipjack Heritage Museum and a small marina where volunteers are overseeing the painstaking, knuckle-by-gnarled-knuckle restoration of the City of Crisfield, a 73-year-old skipjack as hallowed to seafarers as the Baltimore oriole is to birdwatchers.

“We want the young folks to learn what it was like when we grew up,” Bob Shores, treasurer of the museum and a native of Deal Island, says with a touch of whimsy. “Skipjacks are the main thing, certainly, but it’s about the owners and their families, the churches, the community and the unique culture here.”

TAKING ON WATER

While the skipjack is the official state boat of Maryland, it’s doubtful that many landlubbers could properly identify one, if so challenged.

First, though, a story.

Whitelock, who has restored several skipjacks through the years, took a party of about 20 passengers into the bay a few years ago as part of a pleasure race. Jostling for position, he clipped a buoy, and the boat started taking on water.](https://media.co-opliving.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/30121310/3-1791174763-62b3f40e7c7cc.jpg)

“We had a fire company, and the Coast Guard or somebody else came to us with these huge pumps. I had a lady on board who was 90 years old and she was in a wheelchair. She was the most calm of anyone on the boat. In a couple weeks time, I got a letter from her and she said, ‘Stoney, thank you for the trip. I really enjoyed it. That’s the most excitement I’ve had in 50 years.’”

The skipjack — the name likely came from a fish — appeared in the 1890s as a working boat, an offshoot of crab skiffs used to harvest seafood in the Chesapeake Bay and surrounding areas. It was well-balanced, with the length of the boom equaling the length of the deck, suitable for a crew of five or six. Light and mobile, with a V-shaped wood hull and a single mast with two sails, the skipjack was ideal for trawling shallow waters and dredging oysters during the winter months.

Chuck Collier is helping to restore a skipjack owned by his uncle and legendary captain Art Daniels Jr. (Photo By: Jim Robertson)

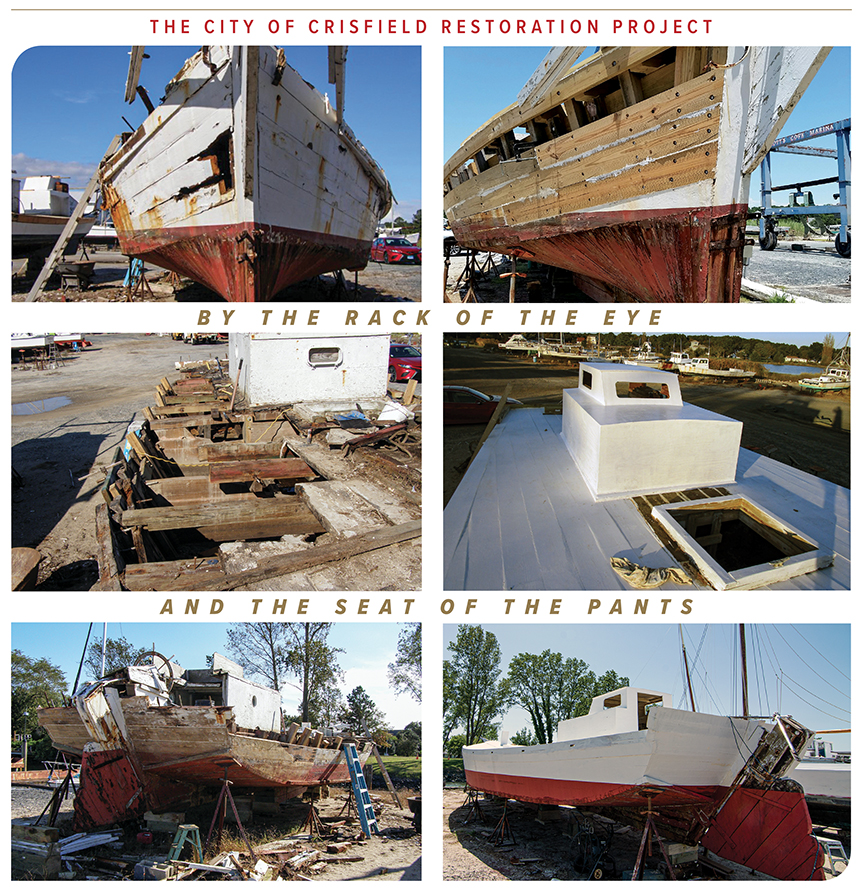

“By the rack of the eye and the seat of the pants” is the way veteran waterman Curtis Applegarth of Talbot County described the construction of a skipjack while he was building and rebuilding boats in the mid-20th century. The rack referred to the craftsman’s ability to identify lines for watertight fits; the pants were what the craftsman sat on during times of frustration.

Given basic carpentry skills, skipjacks were inexpensive to build with a minimum of tools. With a vintage ax he has donated to the museum, Shores demonstrates how old-timers straddled logs and shaved wood, swinging like a pendulum until they reached perfection. “Can you imagine that?” he asks. “You’d think your legs would be torn up.”

Estimates of the peak number of skipjacks vary widely. Some sources put the number as high as 2,000 during the boat’s heyday; a more realistic number seems to be the 400-500 range that the Baltimore Sun reported existed around 1915.

By the 1970s, the fleet had dwindled to fewer than 40 because of declining oyster harvests and aging boats. Not a single new skipjack entered service in the Chesapeake between 1956 and 1979 until the Dee of St. Mary’s, now part of the Calvert Marine Museum, launched on the western bay. About two dozen sail today, with half of those used for seafood harvesting and the rest for leisure and exhibition.

Many owners simply abandoned their boats in side channels or on land, which is how Whitelock came upon a steering wheel from the Mamie A. Mister, now used as a photo op at the museum.

“The boat was up in a field in Easton. It was wrecked. The guy who had it was going to redo it, but you know how things get,” Whitelock says, brushing his hand on the old wooden wheel. “I wrestled that thing off and threw it in the back of my truck some kind of way. It was all rotted and I redid it.”

MUSEUM PIECES

The skipjack wheel has that “wow” factor Shores says he was hoping for when the museum opened May 8, 2021, in a one-time country store. Behind it is a trove of model skipjacks and boats produced in minute detail by owners, artisans and hobbyists, as well as photographs, sketches, sailing logs and artifacts that document the history of Deal Island.

The Skipjack Heritage Museum in Chance, Md. (Photo By: Jim Robertson)

The journey to that day, however, was about as speedy as its namesake boat on a windless afternoon, which is to say agonizingly slow.

In the 1970s, Shores inherited a trailboard, the ornamental piece that runs along the bow, from his grandfather’s boat. “I thought, ‘It’d be great to have a place to put some of these things. I’d love to have that in a museum’ and that’s the way it was for a lot of folks.”

The local Lions Club raised some money and supported the initiative, but it ended, as Shores jokes, “dead in the water.” A few Lions Club members and interested parties reorganized in 2007 and selected a new board of directors; seven years passed until the group bought the country store and tried to convert it to a museum.

The state of Maryland came through with a $75,000 grant. That brought cheers throughout Chance until museum board members read fine print that required state approval of building alterations, such as replacing worn-out wooden floors or a rusty tin ceiling. “When they left, we had a meeting,” says Shores, an accountant by trade. “We decided to send them a letter saying, ‘Thanks, but no thanks. Here’s your money back.’”

In 2018, workers tore down the country store and started the process of building a museum. Donations poured in, and not just of cash and challenge grants. A lighting contractor provided 48 lights; a Salisbury store chimed in with 53 gallons of paint. “I think the Lord opened the floodgates for us,” Shores says. “I see us adding on to this building. There’s not enough room. We’re filling filling up right now and we’re getting more stuff all the time.”

Like the horse-drawn hearse. A funeral home operated in the area for three generations, starting in the 1880s with the kind of lighted hearse you’d associate with the procession for a head of state. “He definitely had a horse-drawn hearse and that’s the story, that a man, Mr. Webster from Deal Island, gave it to us,” Shores says. For now, it’s in safekeeping in Whitelock’s yard.

DAYDREAMERS

Chuck Collier and his schoolmates pressed against a second-story window at Deal Island High School to watch the skipjacks during winter harvest, their sails ballooning against the watery blue backdrop. How, they wondered, did the boats dance across the bay when the wind blew in only one direction? “I think all of us were daydreaming when we were in high school,” Collier says more than 60 years later.

Dreams collided with reality when he was a lad of 16 or 17. “We were dredging shells. These dredge boats, all they did was load that dredge up every four minutes. It came up loaded with shells and you have to shove them back on the deck. There were 854 bushels and this was before lunch. The captain said, ‘We can get another load.’”

Collier shakes his head at the memory. “When I came home, I said, ‘Well, I don’t know if I want to do that.’”

He relates this story while walking the 45-foot length of the gleaming, white-coated City of Crisfield, a skipjack built in 1949 in Reedville, Va., and owned for most of its working life by Art Daniels Jr., his uncle and a legendary captain in these waters.

Daniels died in 2017 after skippering into his 90s, so Collier places a premium on the museum’s rehabilitation of the Crisfield. He gets a little choked up when he sees the burn pile in the back of Scott’s Cove Marina, knowing that could have been the final destination of an untended Crisfield, taking with it the passion of his uncle.

Life on the water had its charms and its challenges. “We did the boat deal and the oyster deal and the crab deal. There wasn’t anything else to do here; it was the only industry,” Whitelock says. “It was hard work, but it was rewarding. You were out in nature every day of your life. So it’s all good.”

At the same time, watermen had to coexist with forces of nature, low prices, poor bay conditions and parasitic oyster infections. In winter months, Collier recalls, his uncle and other captains sailed north for four or five days at a time, living on the boat and returning on weekends. “They couldn’t make a living around here. It was a different era,” he says.

During one five-year stretch in the 1960s, MSX, a disease known as the “white death,” killed almost all the oysters in Maryland’s Tangier Sound and the Virginia portion of the bay.

The City of Crisfield under restoration. (Photo By: Jim Robertson)

By the early 1990s, the bay, which once supplied one-half of all oysters in the U.S., produced 1% of what it did in the 1890s.

A lot of would-be watermen thus ventured afield. Collier worked at DuPont for nine years, then moved to Florida with his wife Linda as a commercial fisherman with 1,100 lobster pots, before they returned to Maryland and joined the museum board.

Whitelock learned overhead line work with the Seabees in Vietnam. He landed at C.W. Wright, an electrical contractor, for $3 an hour in 1970 before starting his own business and contracting for years with Choptank Electric Cooperative and A&N Electric Cooperative.

Now, the Crisfield and the museum have become a rallying point for the greatest generation of skipjack captains. After Daniels died, the museum took ownership of the City of Crisfield, which had deteriorated far from the mastery of the bay it displayed in winning nine Labor Day skipjack races from 1965 to 2008.

A donation of $5,000 from Choptank Electric is helping to underwrite the all-volunteer effort. “This is an important part of the heritage of the Eastern Shore and we’re pleased to contribute in a way that brings back memories for past generations and creates new ones for the future,” says Mike Malandro, president and CEO of the cooperative.

Collier and his colleagues have applied their share of elbow grease to the project. His wife says she watched in amazement as they took 15-foot-long moistened pine boards, clamped them every 18 inches, drilled holes, and precisely fit the planks to the exterior. “Within an hour, they had bent it to match the design of the boat. That was impressive,” she says.

To Collier, it is a way of keeping his uncle’s prized boat from the burn pile. “I would have been sorry if we didn’t do something with the boat,” he says. “All of us leave our trails somewhere.”

For more, visit skipjackheritage.com.

Poet of the Chesapeake

HE WAS NICKNAMED “DADDY ART,” but Art Daniels Jr. was more than daddy. He was the first father of Chesapeake Bay skipjacks. Born in 1921, he followed his dad’s footsteps into skipjacking, gaining his greatest fame with his City of Crisfield boat.

Maryland Public Television featured him in three productions and executive producer Michael English said Daniels “sort of epitomized the legend of the Chesapeake Bay skipjack captain” after he died in 2017 at the age of 95.

“Yes indeedy, it’s still fun workin’ on the water,” Daniels told Chesapeake Bay Magazine. “It’s an adventure, greatest thing in the world. You’re always looking for that oyster goldmine. I’m always lookin’ for that next good lick of oysters.” A deeply religious man, Daniels authored numerous poems. One of them, “The Mariners Song — The Sea,” is on the wall of the Skipjack Heritage Museum. In part, it reads:

Click for video: